We were on our feet, easing toward the door to his office in the state judicial building when Judge Ed Johnson started telling me about a rainy afternoon when he and Zell Miller went to visit the lieutenant governor’s mother in a drab hospital room in Hiawassee, Ga.

Johnson had been a campaign worker in Zell’s first statewide campaign so he had met Birdie Bryan Miller many times, He was familiar with how Zell’s father died when his baby was 17 days old, how his mother reared he and his older sister alone and how Miss Birdie built their house toting rocks from a nearby stream one stone at a time. What he wasn’t prepared for was the decline of this strong mountain woman.

She was in the room even if her mind was somewhere else. She sat in a chair made of naked steel, her frail arms resting on the arms of the chair. Johnson, then a lawyer in Fayetteville, Ga., followed his mentor into the room. Miss Birdie’s face lit up and she asked Johnson to pull a chair closer.

“Zell’s over at North Carolina with his grand-daddy,” she said.

Finally she looked up at her only son. “I don’t believe I know you,” she said.

He was hurting but he hid the sadness. He took her hands and spoke softly. “Yeah Mama, you know me,” Zell said, gently stroking her bony hand.

The three of them were still chatting when a switch turned on in her mind and she recognized her son. She called him by name and started catching him up on the news. “Jane came to see me this morning,” she said. Zell had to laugh for his sister lived in Birmingham. He asked her what they did.

“We went shopping,” she answered.

“How did you keep from getting wet?” he asked. “It has been raining cats and dogs for three days and it hasn’t let up all morning.”

Her answer was direct.

“Zell Miller, it don’t rain where I go.”

• • •

By the time Ed Johnson finished sharing his story, we were both crying. It was 1996. He was a member of the State Court of Appeals. I was a newsman and free-lance writer researching the biography of Zell Miller — by then in his second term as Governor of Georgia. Ed and I went to high school together and he took me to a window and showed me a view of our old Atlanta neighborhood. Between questions, we shared some laughs but by the end we were sobbing.

That story still haunts me. So do her words: “Zell Miller, it don’t rain where I go.”

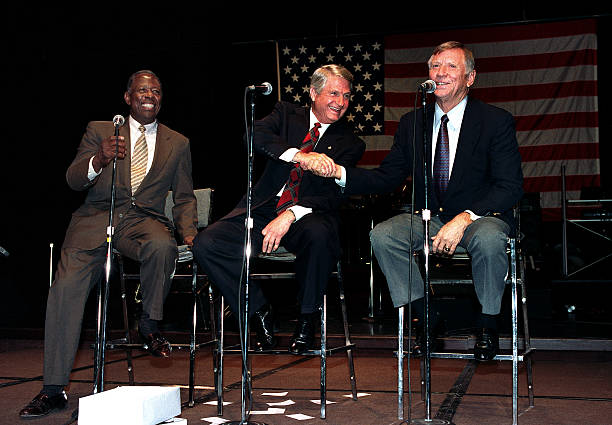

Painting that vivid picture of mother and son, the judge validated the story of Zell’s Mama and that rock house — the house where last Friday Zell Miller died. This week, the story of Miss Birdie and that house surely will be repeated during three separate memorial services that will be attended by a cavalcade of national and state leaders including three former Presidents of the United States. Among the eulogists will be the Rev. Don Harp, a Methodist minister who played on Zell’s baseball team when he was coaching at Young Harris College.

Painting that vivid picture of mother and son, the judge validated the story of Zell’s Mama and that rock house — the house where last Friday Zell Miller died. This week, the story of Miss Birdie and that house surely will be repeated during three separate memorial services that will be attended by a cavalcade of national and state leaders including three former Presidents of the United States. Among the eulogists will be the Rev. Don Harp, a Methodist minister who played on Zell’s baseball team when he was coaching at Young Harris College.

This week, many words have been written about Zell Miller. Even before years of poor health began, he feared such articles, which explains why he tried to manipulate me when I was writing his biography. He did not want to be portrayed as a one-dimensional mountain man in cowboy boots. He could quote Merle Haggard and Flannery O’Connor in a single speech and he could biting write letters to the editor about the Snuffy Smith strip in the funny paper, lambasting editors for the way the strip portrayed folks from the hills.

He wanted people to see his deeper side, how he listened to classical music in his private moments and what a serious historian he was. Sorry Zell, you will be talked about most because of your abiding love for country music — the people who wrote the songs and the artists who performed them — your lifelong obsession with baseball, your support for education and your respect for the United States Marine Corps.

As a professor at Young Harris College, he taught country music singer Ronnie Millsap and in his early campaigns Whispering Bill Anderson helped him draw crowds to his rallies. When he was lieutenant governor, he celebrated his birthday every year during the General Assembly by throwing himself a rowdy party that featured current stars from Nashville.

Zell Miller lurched into a group of flaggers before a George Jones concert in Buena Vista, Ga.

Years later, I was at the Silver Moon Music Barn in Buena Vista, Ga. the night Zell came to hear George Jones. There were more people at that concert than there were in any town in Marion County. It was a meeting of two old friends but there was more to it than listening to The Possum sing “White Lightning.”

Around that time, the governor was trying to change the Georgia Flag and eliminate its Confederate symbols. Some folks in Marion County were part of the organized movement that would help block Zell’s progressive idea. To no one’s surprise, when emcee Johnny Outlaw (AKA Mark Cantrell) introduced the governor the place exploded with boos and catcalls.

What did Zell do?

He left the safety of his seat on the mezzanine, went down the steps and waded right into the middle of the flaggers. They booed him when he was upstairs, but when he was nose-to-nose with them they asked him to pose for a few pictures. Later, when George Jones recognized his friend the governor from the stage, response was much more polite.

* * *

His passion for baseball began with his Uncle Hoyle, who played some minor league baseball in his day. It continued when Zell was the youngest player on the town team. Then, as a college kid, he played shortstop at Young Harris and later was head coach. His offices were always filled with baseball trinkets, including a baseball he caught at the 1995 World Series. His catch was validated by President Jimmy Carter.

“And you know he wouldn’t tell a lie,” Zell joked.

You would think being the keynoter at a national political convention would be a highlight for a lifelong politician. Not really. When he spoke at the Democratic Convention in 1992, that appearance took a backseat to going to Yankee Stadium that afternoon as the guest of former Yankees Hank Bauer and Bill Skowron.

“I’ll never forget coming up the tunnel and seeing Yankee Stadium unfolding before my eyes,” he said.

While we were finishing Zell: The Governor Who Gave Georgia HOPE, he called me early one morning. He was in a car on his way from the Governor’s Mansion to the State Capitol. But government was the last thing on his mind.

“You’ll never guess who I had dinner with last night,” he said. I wouldn’t have guessed and he sounded like a breathless little boy when he told me that he had spent the evening with Ted Williams in Florida. He told me the whole story and shared everything the Boston Red Sox Hall of Famer said about hitting a baseball.

Zell Miller made a quick trip to Florida to pick up artifacts from baseball legend Ted Williams for an auction to help build a new playing field at Young Harris College.

Zell capitalized on his friendship with Mickey Mantle and Hank Aaron to help build a ball park at Young Harris so a team that he helped bring back to life would have a place to play. He did this because of his love for baseball and his commitment to a school that helped rear him.

The Young Harris campus was his backyard when he was growing up. His father and his mother taught there and the faculty there was like an extended family.

As a youngster, Zell was painfully shy. All he cared about was baseball. Until Edna Herren came along, that is. With a fresh flower in her hair everyday and a mesmerizing scent about her, Zell was totally smitten.

It was she who encouraged him to learn grammar and practice public speaking. She pushed him on to the Debate Team where he excelled. Miss Herren was a stickler for the placement of commas and the agreement of nouns and verbs. He responded to her rigid style and became her pet.

The influence of this one teacher was never forgotten and once he got into government he remembered her and how education turned his life around. He would become known as the “education governor” because of the way he fought for teacher raises. He also created the Hope Scholarship and a statewide Pre-K program. He gave every newborn in Georgia a copy of The Little Engine That Could and a classical music CD.

Edna Herren would have been proud.

• • •

What he didn’t learn in school, Zell Miller learned in the Marine Corps.

As a student at Emory and the University of Georgia, he was floundering. So was his life, as shown by a night he spent in a North Georgia drunk tank. The Marine Corps changed his life, a story he told in a book called Corps Values.

Those values were more than platitudes. He was never without a Marine Corps pin in his lapel and he vigorously chided me when I referred to him as a former Marine. Sgt. Miller said there is no such thing as a former Marine. Once a Marine. Always a Marine.

Loyalty between Marines is shown in so many ways.

When his biography was finished in 1997, publishers at Mercer Press arranged a tour of Washington, D.C. We did three book signings and Zell appeared on several national radio shows. He wanted to take me to his favorite restaurant in D.C. — Old Ebbitt Grill — known for its highbrow political clientele and its fresh crab-cakes.

When his biography was finished in 1997, publishers at Mercer Press arranged a tour of Washington, D.C. We did three book signings and Zell appeared on several national radio shows. He wanted to take me to his favorite restaurant in D.C. — Old Ebbitt Grill — known for its highbrow political clientele and its fresh crab-cakes.

When our party arrived, something was amiss with the reservations. I never did know what happened. Zell was not one to wait in line anywhere. He believed that if you were on time, you were late. That was the Marine in him. When he found out what was going on, he went straight to the head waiter. They talked quietly and almost seemed like old friends.

We were soon seated in a choice location.

I figured the man recognized the Governor of Georgia. No. They were both Marines.

• • •

For the past few years, Zell didn’t welcome many visitors to Young Harris. Some of that might have been vanity, for he didn’t want people to see him shakily leaning on a cane. Mostly he just didn’t feel like seeing people. Shingles started it. Then came Parkinson’s Disease, Congestive Heart Failure and a multitude of other illnesses. He took a bad fall at a Young Harris basketball game and another at home. He ended an enjoyable weekly lunch with some old coaches and players. Then came the announcement from his family that he would be making no more public appearances.

When word came of his death last Friday, I wasn’t surprised, just sad. I remembered that feisty look he could flash you and how he lashed out at news reporters who he believed wronged him. The story I’ll never forget followed an article by the late Dick Pettys of the Associated Press. His article reported that Gov. Miller had prostate cancer — which was incorrect.

The next time they saw one another was outside the capitol at the governor’s reserved parking spot. Zell had been waiting for just the right moment. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a rubber glove that he handed to Pettys.

“Next time ask my doctor or test me for yourself.”

Politicians today don’t carry around rubber gloves. Fact is, most of them are boring and bland. In honor of Zell Miller’s passing, I’ll take a page out of his songbook and quote the lyrics to a country standard by George Jones himself. The words are appropriate:

Who’s gonna fill their shoes?

Who’s gonna stand that tall?

Who’s gonna give their heart and soul

To get to me and you?

Lord I wonder, who’s gonna fill their shoes?

Chattooga Opinions

The Joy of the Journey: The Importance of Worship

Bulloch Public Safety

GBI Investigates Child Death in Metter

Bulloch Public Safety

06/09/2025 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

06/23/2025 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

06/02/2025 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

06/16/2025 Booking Report for Bulloch County

Bulloch Public Safety

06/19/2025 Booking Report for Bulloch County